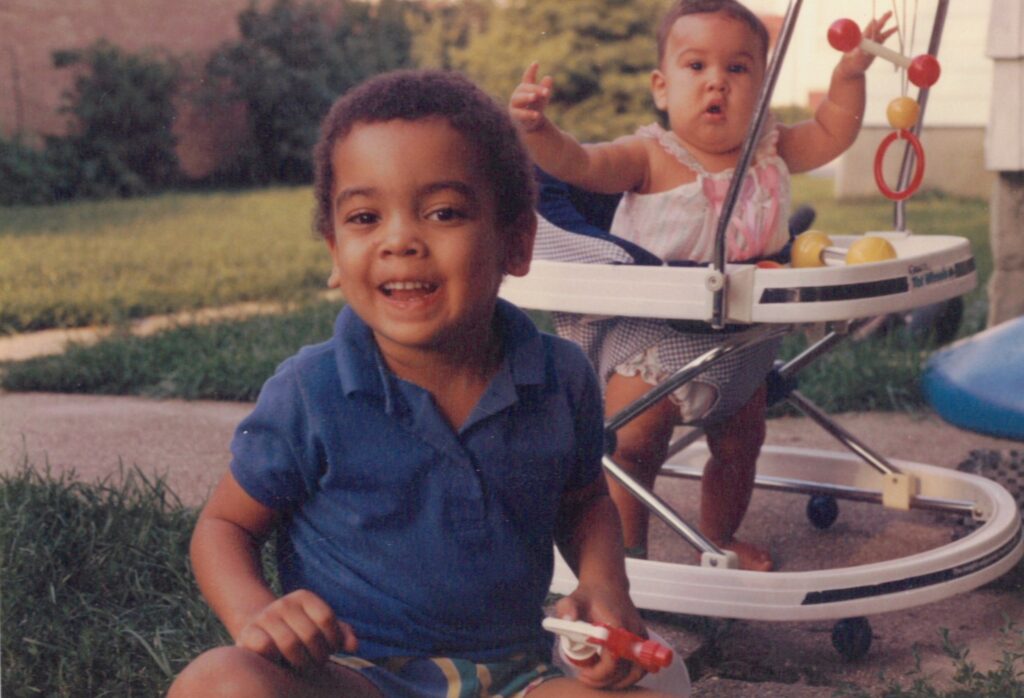

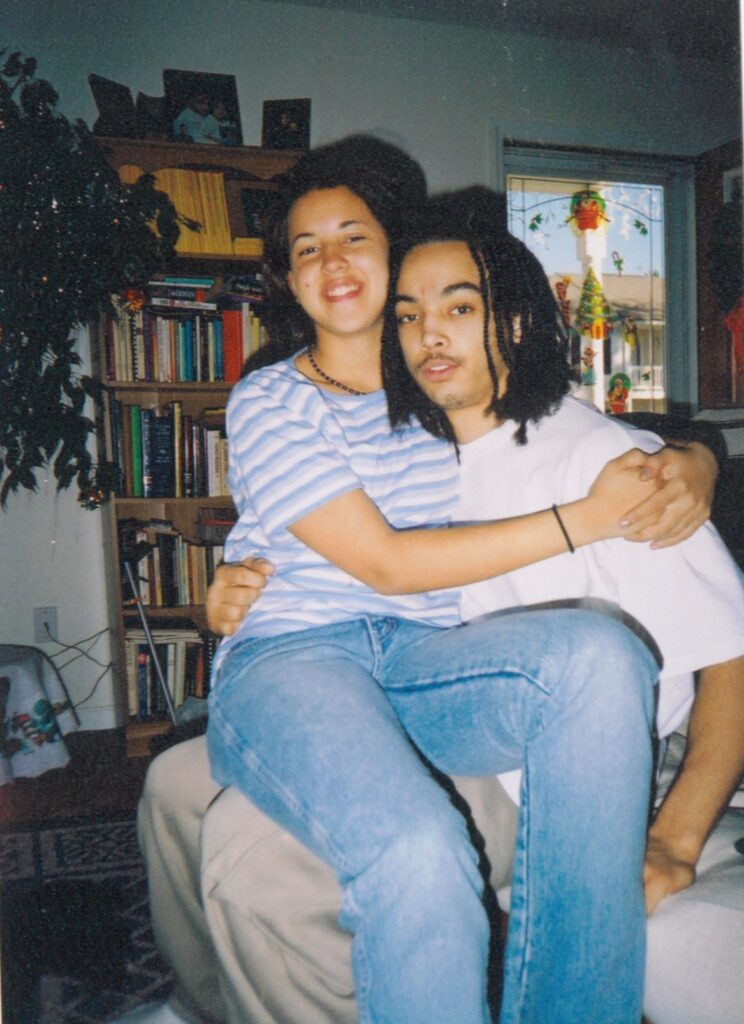

Andre Smith lost his son Daniel, pictured with his sister, to murder. Andre says the death penalty does nothing to heal families or change the societal forces that lead to violence.

Andre Smith lost his son Daniel, pictured with his sister, to murder. Andre says the death penalty does nothing to heal families or change the societal forces that lead to violence.

Andre Smith lost his son Daniel, pictured with his sister, to murder. Andre says the death penalty does nothing to heal families or change the societal forces that lead to violence.

Andre Smith lost his son Daniel, pictured with his sister, to murder. Andre says the death penalty does nothing to heal families or change the societal forces that lead to violence.

If we want to prevent violence, we should focus on restorative justice and ending racism, poverty, and child abuse — not an inhumane punishment that creates more grieving families and traumatized children.

Any response to crime, but especially the extreme punishment of death, should be rooted in evidence-based strategies to make society safer. However, more than three decades of studies on deterrence and the death penalty show no link between murder rates and capital punishment.

The 23 U.S. states that have abolished the death penalty do not have higher murder rates than those that carry out executions, nor do countries that eschew the death penalty. In North Carolina, the death penalty is still on the books but executions stopped 2006. Yet, the murder rate showed no corresponding uptick.

Our close work with death-sentenced people, as well as families who have lost loved ones to violence, confirms that there are more effective ways to prevent murder. The vast majority of those on death row committed unplanned crimes arising out of mental illness, poverty, substance abuse, and trauma. Societal efforts to remedy those problems, along with the racial inequities that underlie them, would have a far greater impact on public safety. Many surviving family members also say the death penalty fails to bring them healing, and they ask that the state not kill in the names of their loved ones. Practices like restorative justice are designed to address harm and bring healing, rather than focusing on retribution.

We must end the inhumane death penalty because it serves only to perpetuate violence and suffering.